The Cold War was a fascinating time for doctrinal development and is crucial for understanding how and why we have the doctrine we do now, particularly as we start looking at whether we can fight peer-state adversaries. So I’m going to revisit Cold War battle plans, talk about how they’ve changed, and how technology and doctrinal changes drove that change.

Specifically:

- The Fulda Gap;

- The Strategic Picture;

- 7 Days to the Rhine (Part 1):

- Tactical Nuclear War,

- Readiness,

- GIUK Gap;

- Western Doctrine (Part 2):

- Defence in depth,

- Active Defense,

- AirLand Battle,

- Full Spectrum Operations;

- Where next?

The Fulda Gap

It’s 1979. Germany is divided: on the West the combined NATO forces of the US, UK, West Germans, Belgian and Dutch. On the East are the East German, Polish, and the forces of the USSR (with the Czech to the south). If the Warsaw Pact is to advance into NATO territory then it must do so through West Germany, because it’s here that US reinforcements will arrive and they must not be allowed to arrive.

A funnel created by the neutral states of Austria (still expected to probably be invaded by the Warsaw Pact), Yugoslavia, and the Baltic means everything comes down to the East / West Germany border. The topography of Germany means that the North is preferred – wide open plains are ideal for the mechanised forces of the Warsaw Pact, but initial US reinforcements will fly into the major USAF base of Frankfurt in the South until the heavy armour arrives by sea.

In the way of a Warsaw Pact advance, between the defending US V corps in the Central Army Group and the advancing Soviet 8th Guards Army are the Rhön mountains and the Vogelsburg. In the narrow valley between the two lies the small city of Fulda.

If the Cold War had ever turned hot then this small city would have been obliterated.

The Strategic Picture

The Group of Soviet Forces in Germany existed for one (stated) reason: to prevent the ‘inevitable’ war from spreading into the USSR itself. The minute things kick off, no matter who starts it, the Soviet forces are getting across that border and ruining someone else’s house thank you very much. Unsurprisingly, the rest of the Warsaw Pact backed up this plan. Nobody can win the eventual war by steamrolling over the other military and invading the motherland, so what does victory mean?

The end game, the whole plan of WWIII, is to both avoid total nuclear annihilation and to be in the stronger position such that when the UN steps in one team is awarded better terms in the inevitable peace. That gives two victory conditions:

- If you are USSR then you must grab as much land from NATO as possible and prevent reinforcement by the US.

- If you are NATO then you must halt the Soviet advance and defeat it in detail. You must keep US reinforcement lines clear, so that heavy armoured units held at lower readiness can reach Europe.

7 Days to the Rhine

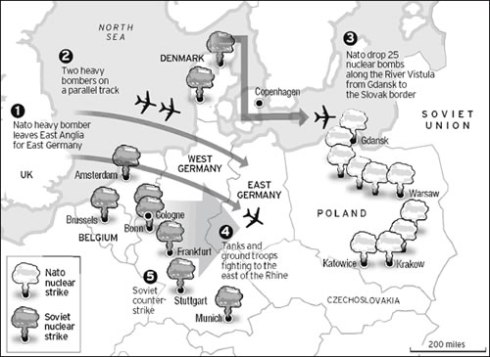

You are the USSR. High tensions suddenly, unexpectedly, lead to war as NATO launches a series of nuclear strikes on the Vistula River in Poland, cutting off access to Poland and East Germany from forces in the USSR, and invades East Germany (a common planning scenario involves an enemy first strike). Your first move is to shift the fight to NATO: break civilian morale, pour troops over the border, and deny the Atlantic to US reinforcement convoys.

This is in fact the exact story of a 1979 Soviet battle plan which aims to present a fait accompli to the US and UN by arriving at the Rhine in D-Day+7, and getting to Spain by D-Day+14. In the 10 years since release there has been some great analysis of the plan. There are three interesting elements that are worth a mention here:

Tactical Nuclear Strikes

Soviet doctrine assumed that both sides could use widespread tactical and strategic nuclear strikes without escalation to full strategic nuclear war (ending in Mutually Assured Destruction). This isn’t at all what NATO assumptions were, so it’s good that nothing ever did kick off because NATO would have escalated. The initial NATO nuclear strikes along the Vistula assumed a mindset in which Poland’s populace was seen as a forgivable casualty of war to effectively degrade the Soviet ability to reinforce the frontline, again, very at odds with mainstream NATO thinking (especially in a first strike scenario). There were some very interesting tactical nuclear weapons created by both sides.

Because of this planning assumption a lot of cities are in the firing line: NATO destroys Warsaw and 10 other major Polish cities, as well as a number of other Warsaw Pact cities; the Soviet response targets major population centres and military targets to break morale.

Interestingly, though the Soviets target many expected countries (Germany, Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands), they also target Austria (a neutral state), Italy (nowhere near the battle area, but able to launch a counter-attack via Austria), and do not target France or the UK! France by this point had stepped outside of the NATO military planning set-up, but the UK was a key part of NATO plans – hosting US nuclear weapons and defending the Atlantic resupply routes.

Both NATO and Warsaw Pact forces expected to fight in areas which had been subjected to nuclear strikes (in fact the full spectrum of Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical (NBC), or as it’s now known Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear (CBRN)). Both sides undertook testing on the nature of fighting in an irradiated area, the Soviet Union in the Totskoye nuclear exercise, and the US through the Desert Rock exercises. The requirement to fight in a CBRN contaminated area drives British armoured vehicles (including Challenger II tank, Warrior armoured fighting vehicle, and others) to contain a kettle – allowing troops to live on boil-in-the-bag meals and continue fighting for up to three days.

While talking about nuclear tests it would be remiss of me to not bring up potentially the first thing to make it into space (it probably didn’t).

Readiness

The Soviet plan assumes that after an initial NATO attack they can mobilise their forces, counter-attack East Germany, and fight through NATO positions to reach the Rhine in 7 days. Bearing in mind the logistic tail and replacement of casualties (high), that timescale is absurdly fast. Soviet forces were kept at a high readiness, with follow-up reinforcements not far behind – snap exercises were called periodically to test readiness, and these continue to this day in Russia at a much larger scale than in many (possibly any) NATO countries.

This plan (real name “CSLA Plan of Action for a War Period”) does not contain any thoughts on how NATO’s first strikes would degrade forward fighting units. It also doesn’t contain any thoughts on Warsaw Pact losses as they fight through the NATO defence – indeed a core tenet of the plan is that NATO’s defensive plans are a sham. Still, the assumptions required to even begin to consider reaching the Pyrenees in 14 days indicate an impressive ramping up of military effort.

NATO’s plan in West Germany requires holding off the Warsaw Pact for 14 days until US high readiness troops can arrive. Some airmobile troops will be available sooner, but given the roughly 7-day Atlantic transit time this assumes that the majority of US armoured forces in the first wave of reinforcements aren’t ready to set sail for a week. This is significantly slower than Soviet planning assumptions.

The GIUK Gap

The Greenland – Iceland – UK Gap is the name of the set of straits through which any vessel from the Baltic or Northern Soviet fleets wanting to enter the Atlantic would have to travel. Given that the entire NATO plan hinges on getting seaborne reinforcements from the US, Soviet ships, submarines, and aircraft very much did want to pass through those straits. In the event of war Soviet submarines would attempt to track and interdict US ships, while Bear bombers launched anti-ship missiles from long range after flying around Norway and through the gap.

Bear bombers would frequently test out NATO readiness, and continue to do so (this example notable for the detail on multi-national hand over). The UK was a heavy contributor to defence of the GIUK Gap – particularly in the forms of Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) and aircraft interception.

These requirements drove capability requirements during the Cold War (e.g. the English Electric Lightning – a rapid but fuel guzzling interceptor, or the Type 23 frigate – a specialised ASW platform), and for some equipment which is still in service, such as the Typhoon and Astute-class submarines (ish – actual background is more nuanced).

Detection of vessels in this gap also led to the placement of underwater microphones – the Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS), which the US maintains to this day. Other elements of it include microphones near the Straights of Gibraltar (to intercept the Mediterranean Fleet

Conclusion

This is getting a bit long, so I’ve split it into two. The 2nd part will go through how (primarily Western) doctrine has changed for fighting near-parity forces, and will give my thoughts on what’s coming next.